Art Econometrics

A R T A S I N V E S T M E N T : Recent data sets confirm the upward trend

By Caroline Dixwell Cabot for ARTLINKGLOBAL

See Also: ArtlinkGlobal Auction News Advisories at:

http://artlinkglobaladvisory.wordpress.com/

See Also: ArtlinkGlobal Benchmarks for Designers at:

http://www.houzz.com/ideabooks/22926344

- It has long been held that art cannot be viewed as an investment.

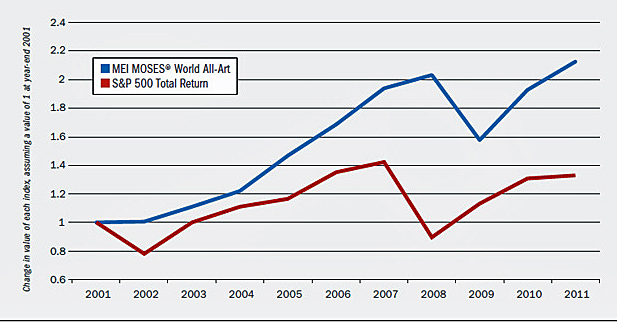

- But this idea is based on old data, pre-internet extrapolations, and concerns over liquidity, authentication and indices methodologies.* Historically it has been true that markets were either too thin or too localized or carried too high a transaction cost to be viable or were skewed by third party financing**. In addition only certain masterpieces commanded the stratosphere which did not obtain for all artists or classes of art. But between 2006 and 2013 the art market’s overall performance widely out paced the S&P and for those who know art history and price movements, the investment has been well worthwhile.

- Today the art market has been “globalized” with a broad inventory base that is widely traded across national borders yet characterized by low volatility. Commissions can be negotiated thereby lowering transaction costs. Private sales can occur through the auction house/dealer and comprise 52% of all art transactions; as such half the market is not reflected in the indices used to track art prices. Third party financing is generally disclosed and is no longer a typical practice.

- Indeed, even beyond the headline paydays (the $43 million Lichtenstein sold for just $2 million in 1988, according to Web site Artinfo), a case can be made for art’s soundness as a legitimate investment-grade asset class. Over the past decade, almost every art category, from stolid old masters to edgy contemporary, has outperformed equity indexes in the U.S. and Europe, according to the Mei Moses index. And in the course of the past half century, the overall art market has about matched the gains of the stock market.

- The internet has dramatically increased transparency, transforming the way in which economists now measure the movement of auction prices across the world. It is as profound a change as I can recite…….a change which heralds an expanding marketplace for “goods” that are both rare and unique. As Mark Twain was fond of saying: “Buy land, they are not making it anymore”.

- Stocks plunged during the recent recession, but the economic downturn’s impact on the art market was minimal. The global equities markets fell 33% over 2009, its biggest drop since 1991. “Despite these uncertainties in the wider economy, the art market rebounded strongly in 2010, especially in China and the US, rising by 52% to €43.0 billion. In 2011 the recovery continued with aggregate values of dealer and auction sales world wide rising by 7% in one year to a high of €46.1 billion. This represents a rise in total of 63% from the trough of 2009.” Worth noting: this isn’t the first time the art market did very well in a downturn – it also out-performed Dow Jones Stock Index during the 2000-2001 recession.

-

The art market has now enjoyed eight years of price appreciation. According to Bloomberg, the average compound annual return has been 33% since 2004. The high historical performance has attracted the attention of both ultra-high-net-worth hedge fund managers and middle income individuals. It has prompted a new analysis of price data performance for art and antiques in the digital age, and this study of price movements has changed the way we think about this asset class.

- Quite recently Dutch, French and German economists have mined this new data, applying mathematical and statistical methods to uncover the central and motivating relationships between economic conditions and the way in which we price beauty.

- There is no question that an investment approach to the purchase of art has now been transformed by the expanding market liquidity of trans-national auction houses and the rise of the super-rich***. This liquidity has been tied in the past to the boom/bust cycles in specific economies, a topic studied by Vikram Mansharamani, PhD and lecturer at Yale. He links Sotheby’s high stock price to imminent declines in the stock market: 1991 (Japanese asset price bubble), 2,000 (dot com bubble), 2007-9 (credit default swap bubble) were all years when the super-rich added liquidity into the art market, and this rise in art prices signaled the subsequent collapse in stock prices. Today, however, liquidity is generated across borders so that the super-rich are not dependent on one economy; indeed, with the advent of Central Bank intervention in 2008 and 2010, now economies across the globe have access to unprecedented monetary largesse with consequently greater ease of transfer for a “commodity” long thought to be hobbled by thin or localized markets .

- In addition the art market is driven by the “once in a lifetime effect”, that is to say there are a finite number of masterworks and an infinite number of wealthy bidders. This pricing phenomenon is rarely observed in other investment commodities; as long as the economic landscape continues to be dominated by multinational corporations, the presence of the super rich at the auction table will influence the way we value art. As old master paintings become ever more rare, prices will rise to historic levels.

- It bears repeating as well that the reputation of the artist and the strength of the attribution to an artist, the topic of the work (significant premiums for self-portraits and urban scenes), matters as well as the size, the medium, and the degree of visible authenticity (signature, date). Prices are strongly correlated with the timing of the sale, and the identity and location of the auction house: especially pieces sold at sales in May/June or November/December at Sotheby’s or Christie’s in London or New York.

- Finally multi-national galleries such as the Gagosian model, coupled with the expansion of the auction houses—from opening worldwide branches, to initiating private treaty sales and primary market exhibitions such as Sotheby’s S2 gallery as well as the proliferation of art fairs opening each and every month at a location near you, all helped to create a new world order with art at the forefront of a new class of investments. Though they may be labeled variously as ‘Passion’ or ‘Treasure’ assets, under any guise, you have a phenomenon that is now approaching tsunami scale. Because of the liquidity baked into the system and the unprecedented rise of the ultra super rich, there is a high probability that demand will continue to outstrip supply as we see this year in prices for old masters.

*The Mei-Moses series for the All Art Index dates from 1875 measured on an annual basis and from 1965 on a semi-annual basis. The MM All Art Index is computed using repeat sales initially sold at auction by Sotheby’s and Christie’s.

**A guarantee typically operates as it sounds. When someone offers a piece for auction, the house will sometimes guarantee that the seller will make at least a minimum amount by arranging with a third party to purchase the work for a specific price, undisclosed to the public, should it fail to sell for more. In exchange for putting up the funds, the guarantor, whose name is also not revealed, gets a cut of any proceeds above the guarantee.

***”Excluding earnings from investment gains, the top 10 percent of earners took 46.5 percent of all income in 2011, the highest proportion since 1917, Mr. Saez said, citing a large body of work on earnings distribution over the last century that he has produced with the economist Thomas Piketty of the Paris School of Economics.” Annie Lowrey, The New York Times

- Economist and Art Historian:

- Proprietary search, authentication and strategic implementation at auctions worldwide